About the Author

Monica Chen is a native Taiwanese violinist and the first practitioner of dystonia in Asia. She has a DMA in violin performance and currently working as an assistant professor at Taipei National University of Arts. Monica studied with Dr. Farias, a leading specialist treating dystonia with movement therapy. She is also the Chinese translator of Dr. Farias‘ book, ‘Limitless’.

I recently finished the page introducing the Dystonia Recovery Program (DRP) and happened upon this fascinating article: “Treatment of spasmodic torticollis by a psycho-motor retraining: a method developed 100 years ago by Henry Meige.” I found it contained many points worthy of reflection and wanted to share them with you.

This article highlights a treatment approach for cervical dystonia documented a century ago by French neurologist Henry Meige (1866-1940). He is renowned for his work on craniocervical dystonia, which led to the eponym Meige syndrome (encompassing blepharospasm, oromandibular, and facial spasms).

A hundred years ago, before Botox injections or other drug treatments were available, Dr. Meige utilized a therapy called “Psycho-Motor Retraining” (“discipline psycho-motrice”) to treat patients. Key focuses of this training included:

- The patient becomes actor of his treatment.

- The patient needs to have a regular life.

-

The patient had to exercise in front of a mirror 3 times a day.

- Two types of exercises: immobility and slow, deliberate movement.

Today, Botox injection is the mainstream treatment for cervical dystonia. While Botox is effective, it has limitations, and its efficacy varies greatly among patients. My goal here is not to debate Botox, but to prompt a re-evaluation: when passive injection becomes the primary treatment, patients may overlook the necessity of becoming the chief participant in their own recovery. Dystonia rehabilitation requires a multi-faceted approach—adhering to a regular lifestyle, managing sleep and nutrition, and performing daily movement exercises—all of which demand the patient’s active involvement.

The “mirror exercises” are another noteworthy component. Over a century ago, patient self-directed movement training was central to Dr. Meige’s therapy. Strangely, after the rise of Botox, movement training was often excluded from mainstream medical options, leading many patients to be told by doctors that “rehabilitation is ineffective.”

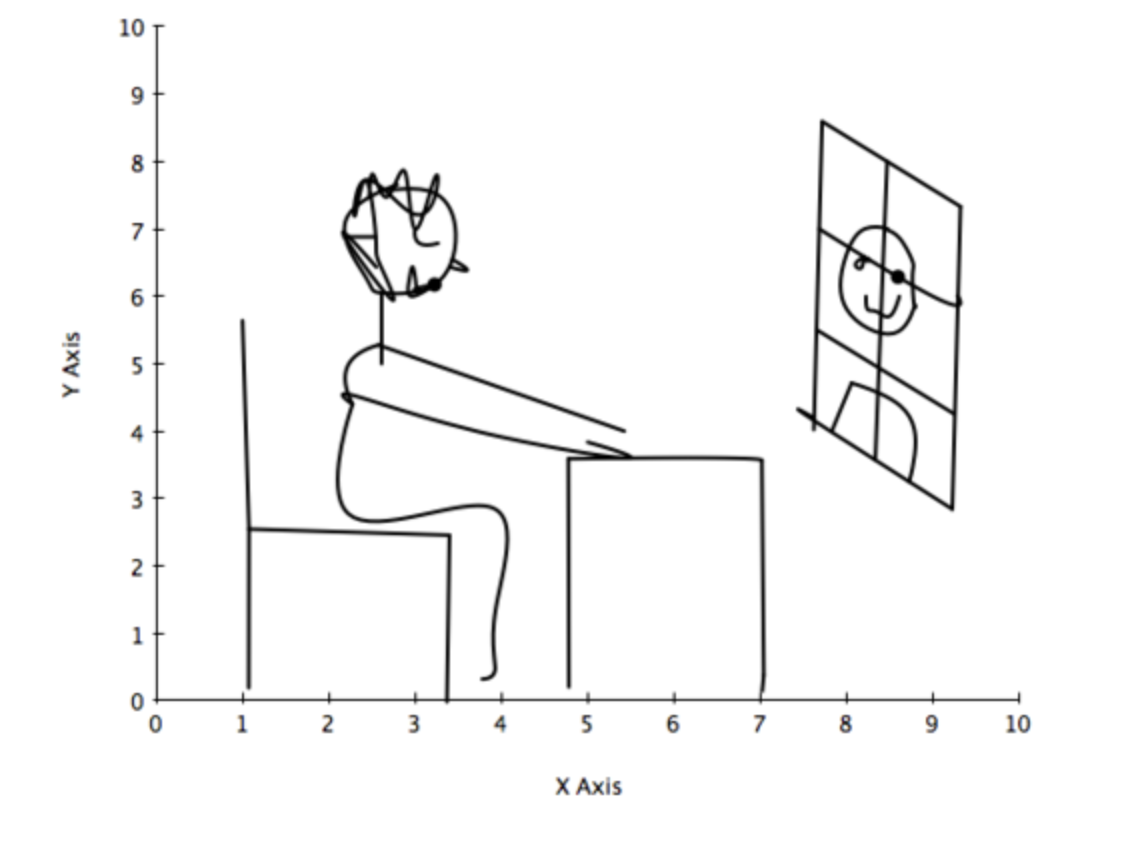

Dr. Meige’s mirror practice was brilliant: he marked the mirror with three lines (as shown in the original document): one vertical line through the center of the face, and two horizontal lines across the eyes and the base of the neck. By observing themselves directly, patients could become aware of their head deviation and the necessary range of movement. He required patients to practice three times daily, seated without back support, with hands flat on a table.

He specified two types of exercises:

- Immobilization: Holding a still position for 5 seconds, repeated 10 times, with 15 seconds of rest between each repetition, gradually increasing the holding time by 5 seconds each day.

- Movement: Performing slow, smooth movements (avoiding sudden jerks or saccades) in rotation, lateral flexion, forward flexion, and extension. This included exercising the shoulders, arms, and torso, alongside muscle relaxation. Patients also practiced writing, reading, breathing, speaking, and daily tasks in front of the mirror.

Dr. Meige’s “Psycho-Motor Retraining” was essentially a training method that combined psychological cognition and physical motor control. This approach surprisingly shares similarities with the neuroplasticity-based movement training developed a hundred years later. Dystonia patients often suffer from sensory and proprioceptive deficits alongside motor control problems. Mirror practice provides a clear, objective visual reference (aided by the drawn lines), allowing patients to observe and correct even minor degrees of head tilt.

Furthermore, I am stunned by the principles of Dr. Meige’s movement training: exercises were counted by the second, repeated multiple times, with a 15-second rest between each repetition. These training principles are entirely focused on neural training, not muscle training. This combination of short duration, high precision, and controlled repetition is exactly the key to successful neuroplasticity training.

The two exercise types he requested are clearly essential for cervical dystonia patients’ motor control. The immobility exercise, though seemingly simple, is immensely difficult for patients; just practicing holding the head still in the center can cause a patient to sweat profusely. The slow, smooth movement practice in three axes presents another huge challenge. Only through neural differentiation—the process of fine-tuning motor control ability—can patients actively learn to precisely control their movements.

Finally, Dr. Meige’s treatment held one more profound lesson: he did not center the entire training on the head and neck. He adopted a holistic view, addressing dystonia from multiple perspectives, requiring patients to activate other body parts, practice muscle relaxation, and engage in self-management of their daily routine. I believe this kind of holistic treatment represents the true model for dystonia rehabilitation. To narrowly focus only on the head and neck is to disregard the complex neurological issues underlying the disease—it is like seeing only the tip of the iceberg while ignoring the massive structure beneath.

A century later, we turn our gaze to the present: How do the latest neuroscience-based rehabilitation methods work? We invite you to continue reading the ‘DRP Dystonia Recovery Program: A Complete Platform Guide‘ to gain an in-depth understanding of this new, comprehensive treatment approach!